10 Barbarian Tribes That Changed European History Forever

When we hear the word “barbarian,” it often brings to mind images of fierce warriors storming through ancient Europe, leaving chaos in their wake. But what exactly did this term mean? Originally, it was used by the Greeks and Romans to describe anyone outside their “civilized” world—basically, anyone who didn’t follow their customs or speak their language. Over time, the label stuck to groups that weren’t Christianized or didn’t fit into the European way of life. Think of the Huns, Mongols, and Vikings—these are the classic examples that come to mind when we talk about barbarians.

But here’s the thing: history is full of lesser-known tribes that also made their mark on Europe, often in dramatic and terrifying ways. Whether they arrived by land or sea, these groups seemed to have a knack for keeping “civilized” Europe on edge. From relentless raids to full-scale invasions, their stories are both fascinating and a little unsettling.

So, let’s dive into the world of these often-overlooked barbarian tribes. You might be surprised by how much they shaped the history we know today. And who knows? You might even find yourself wondering if “barbarian” is just a label the winners used to describe the ones they couldn’t control.

10.The Chatti

When the Romans started expanding beyond Italy, they bumped into all sorts of tribes they’d never met before. One group that really stood out? The Germanic tribes. These guys were tough. It wasn’t until Julius Caesar’s time, during the Gallic Wars in the 1st century BC, that the Romans finally figured out how to tell them apart from the Celts. Fast forward about a hundred years, and one Germanic tribe, the Chatti, became one of Rome’s biggest headaches in the 1st century AD.

Now, if you want to get a sense of just how intense the Chatti were, you’ve got to check out what Tacitus, a famous Roman historian, wrote about them in his book Germania. He didn’t hold back. He described the Chatti as having “strong bodies, sharp features, and a kind of wild energy that made them seem almost superhuman.” But what really makes this tribe fascinating—and a little terrifying—is their unique tradition for young men.

Here’s the deal: when a Chatti boy became a man, he’d stop cutting his hair and beard. This wasn’t just about looking scruffy; it was a vow to the god of courage. The only way he could shave it off? By killing an enemy in battle. Tacitus paints this vivid picture of a young warrior standing over the body of his fallen foe, finally revealing his face to the world. And if you didn’t fight? Well, you’d be stuck with that shaggy look forever, a walking symbol of shame.

But it wasn’t just the young guys who were hardcore. The older Chatti warriors were just as fierce. They were always the first to charge into battle, leading the front lines with a kind of intensity that didn’t fade, even in peacetime. Tacitus says these veterans had this permanent, almost scary look on their faces, like they were always ready for a fight. And they kept that energy up until they were too old to lift a sword.

By the 3rd century AD, the Chatti had joined forces with other tribes to form the Franks, but their legacy as one of Rome’s most formidable enemies lives on. It’s wild to think about how much effort the Romans put into dealing with these tribes, and how much respect they had for their enemies’ courage and strength.

9.The Harii

Tucked away in the eastern parts of what’s now Czechia, Slovakia, Southern Poland, and Western Ukraine, the Harii were a mysterious bunch. They lived far from the more “civilized” parts of Europe, so not much was written about them. But what we do know? They were absolute masters of war—just not in the way you might expect. Unlike the Chatti, who were all about raw bravery, the Harii played a totally different game. Their secret weapons? Camouflage and mind games.

According to Tacitus, the Roman historian, the Harii had a seriously eerie battle strategy. They’d paint their shields black, dye their bodies dark, and only fight at night. Imagine this: you’re a soldier, and out of the pitch-black darkness, a shadowy army emerges, looking like something straight out of a nightmare. Tacitus says their “ghoulish” appearance was enough to terrify anyone. He even claims that battles were lost the moment enemies laid eyes on them. Talk about psychological warfare!

Who exactly were the Harii? That’s where things get tricky. Some experts think they were a small Germanic tribe, part of a bigger group called the Lugii, which itself was part of the Suevi confederation. Others argue they might have been Celts who were around before the Germanic tribes moved in. And then there’s the wildest theory: some scholars believe the Harii weren’t even a tribe at all. Instead, they might have been a special force of young warriors who worshipped Odin (or Woden, as they called him). These guys were supposedly inspired by the Einherjar—mythical ghost warriors chosen by Odin to fight in Ragnarok, the epic final battle of the world.

Whether they were a tribe, a cult, or just a bunch of really dedicated night fighters, the Harii definitely left their mark. Their tactics were so unique and terrifying that they’ve become one of history’s most intriguing mysteries. If you’re into ancient warriors, eerie legends, or just love a good story about underdogs who knew how to mess with their enemies’ heads, the Harii are worth reading about. It’s one of those bits of history that makes you wonder how much we still don’t know about the past.

8.The Picts (Caledonians)

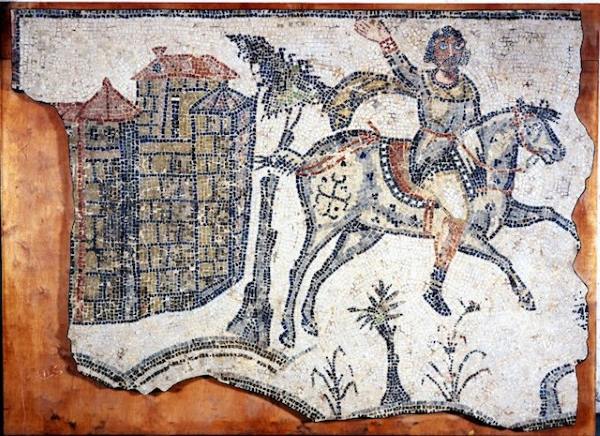

Known to the Romans as Caledonians, the Picts were a people of Celtic or even older origin. Initially used as a pejorative by the Romans, the name Pict literally translates to “painted one.” This was based on their custom of either painting or tattooing their bodies. Yet, by the 7th century AD, the Picts began self-identifying as such. They lived in present-day northeastern Scotland and came in direct contact with the Romans after their invasion of the island.

Around the year 80 AD, roughly 40 years after the initial Roman invasion of Britain, Roman governor and general, Julius Agricola, started the invasion of Scotland. Although they won the Battle of Mons Graupius against the Picts, the Romans didn’t follow up and retreated instead. Modern scholars speculate that the battle didn’t go exactly as was recorded by the Romans, which is further corroborated by the fact that they made very few other attempts at conquering Pictish lands. They, instead, switched to a containment strategy by building Hadrian’s Wall in 122 AD, and the Antonine Wall further north in 142 AD.

According to the Roman soldier and historian, Ammianus Marcellinus of the 4th century AD, the Picts were “roving at large and causing much devastation.” Their go-to military tactics were primarily hit-and-run. They feigned retreat as soon as a battle started and while the Romans were setting up camp later in the day, the Picts would pour out of the woods and attack them. They would also lure the Roman cavalry into traps by following similar tactics.

7.The Vandals

The Vandals were another Germanic tribe originally from present-day southern Poland, which began migrating West with the arrival of the Huns at the start of the 5th century AD. They invaded Gaul and moved into the Iberian Peninsula, settling there in 409 AD. By 429, however, they were driven out by the Visigoths, crossing the Strait of Gibraltar into Northern Africa. In 435, they became clients of Rome but only a few years later, they would break that treaty, capturing Carthage and establishing their own autocratic kingdom.

Over the coming years, they conquered the islands of Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, Malta, Mallorca, and Ibiza; effectively taking control of the majority of Rome’s grain supply. Their pirate fleets now also had firm control over the Western Mediterranean. In fact, the Old English word for the Mediterranean was Wendelsæ (Sea of the Vandals).

In 455, they also invaded Italy and captured the city of Rome, plundering it for all its riches. Although it’s well-known that they didn’t destroy any buildings or kill the city’s inhabitants, this act was later used by the French abbot Henri Grégoire de Blois during the French Revolution of the 18th century to come up with the word “vandalism.” In 533, the Byzantines invaded their lands and in a single campaign defeated the Vandal kingdom, ending their reign.

6.The Avars

When you think of fierce nomadic tribes from Central Asia, the Huns probably come to mind first. They stormed into Europe, leaving chaos in their wake. But they weren’t the last. Less than a century after the Hunnic Empire fell apart in the late 5th century AD, another group of horse-riding warriors from the East stepped into the spotlight: the Avars. They might not be as famous as the Huns, but they definitely carried on the tradition of war and destruction—and even introduced some game-changing innovations, like the iron stirrup, to Europe. Oh, and they’re also the reason the Serbs and Croats ended up moving south.

The Avars first popped up in Europe during the reign of Byzantine Emperor Justinian I (527–565 AD). He hired them as mercenaries to deal with other pesky tribes. But after Justinian died, the Avars decided it was time to settle down. They found their new home in the Pannonian Plain—modern-day Hungary—which, funnily enough, was the same place the Huns had set up their empire. Under their leader, Bayan I, the Avars kicked out the Gepids, a local tribe, and started building their own empire, called the Avar Khaganate. Bayan wasn’t messing around, either. Legend has it he killed the Gepid king, Cunimund, and turned his skull into a drinking cup. Yikes.

For the next couple of centuries, the Avars were a constant thorn in everyone’s side. They raided their neighbors, forced tribes to fight for them, and extorted those they couldn’t conquer. Their favorite target? The Balkans, deep inside the Byzantine Empire. They even tried to take Constantinople in 626 AD, though that didn’t go so well. But their luck eventually ran out. Enter Charlemagne, the Frankish king. He crushed the Avars, captured their capital (known as “The Ring”), and hauled their massive treasure back to Paris. By 796 AD, the Avar Khaganate was history.

The Avars might not be as well-known as the Huns, but their story is just as wild. From their brutal tactics to their dramatic downfall, they’re a reminder of how much chaos a determined group of warriors can cause. If you’re into tales of ancient empires, epic battles, and a little bit of skull-cup drama, the Avars are definitely worth a closer look.

5.The Drevlians

The Drevlians – roughly translated to forest dwellers – were an East Slavic people living in present-day Ukraine and Belarus, northwest of Kiev, during the 6th and 10th centuries AD. One thing that seems to have set them apart from most of their neighbors is that, together with the Polyanians (field dwellers), they were the only tribes to have a monarchical rule. Moreover, the Drevlians seem to have “thought in common with their prince,” which hints towards some direct democracy. But this is not what appalled Christian Europe about the Drevlians, nor was it their prowess in battle. It was actually their pagan customs surrounding marriage.

If the Medieval Slavic ecclesiastical writers had only praise for the Polyanians, saying, among other things, that they were respectful towards their wives, parents, siblings, and parents-in-law, the Drevlians were the complete opposite. In The Rus’ Primary Chronicle from the early 12th century, the Drevlians are said to have “existed in bestial fashion and lived like cattle. They killed one another, ate every impure thing, and there was no marriage among them, but instead, they seized upon maidens by capture.”

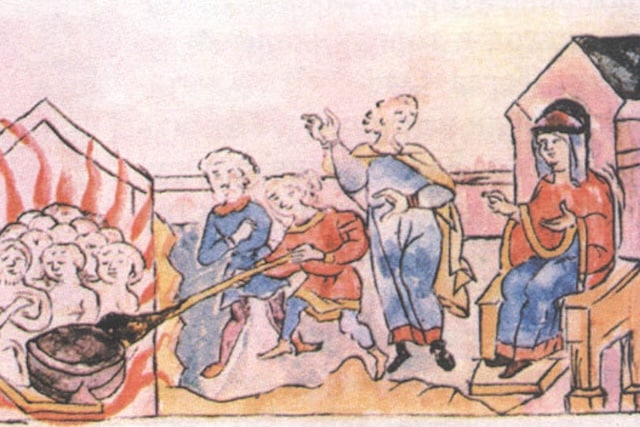

They would meet a brutal end, however, at the hands of Olga of Kiev. After they assassinated her husband, Grand Prince Igor of the Kievan Rus, Olga wanted vengeance. She started by burying the Drevlian ambassadors alive and luring the Drevlian nobles into her bathhouse which was burnt down with them still inside. She then organized a feast in the Drevlian capital of Iskorosten to commemorate her husband, but after everyone got drunk, Olga ordered the people massacred, set the city ablaze, and enslaved the survivors.

4.The Pechenegs

The Pechenegs were a semi-nomadic Turkic people that terrorized much of Eastern and Southeastern Europe throughout the 8th and 12th centuries. During the 9th century, the Pechenegs occupied a large territory between the Ural and Volga Rivers, constantly fighting with their eastern neighbors, the Khazars and the Oghuz. At the instigation of the Byzantine Empire, the Pechenegs began expanding westwards, attacking the Kievan Rus and forcing the Magyars across the Dnieper River and into the Carpathian Basin.

Throughout much of the 10th century, they would fight many battles with the Rus, even killing Prince Svyatoslav I in 972 and turning his skull into a chalice, as was apparently customary with many steppe nomads. It’s believed that during this time, many Slavic people living between the Danube and Carpathian Mountains began migrating north of the Dniester River to escape them. However, the tables would begin to turn by the end of the century, and the beginning of the 11th with the Pechenegs being systematically expelled from the Pontic Steppes, most notably by the Cumans.

It was at that time that they began intensifying their raids into Byzantine territory across the Danube River, even laying siege to Constantinople in 1090. They were, however, defeated by Emperor Alexius I with the help of the Cumans (more on them in a bit), and again at the Battle of Beroia in 1122, effectively putting an end to the Pechenegs as an independent people.

3.The Magyars

The Magyars are believed to be a mixture of Turkic and Ugric people who lived in western Siberia during the first several centuries of the first millennium AD. They would migrate to the southwest around the 5th century and by 830 AD, they crossed the Don River, north of the Black Sea. They were comprised of seven tribes and were later joined by an additional three of Turkic Khazar descent, known as Kavars.

After the Pechenegs pushed them out of the Pontic Steppe, they moved into the Pannonian Plain in Central Europe in 895. They quickly subdued the people living there, defeated the Great Moravian state in 906, and completely obliterated the East Frankian army at the Battle of Pressburg one year later.

For the next 60-plus years, up until 970 AD, the Magyars became the scourge of Europe. They raided and pillaged across most of the continent from present-day Denmark to Spain and Portugal, and from the Balkan and Italian Peninsulas to Western France. After that point, the Magyars became Christianized and in the year 1000 AD founded the Kingdom of Hungary.

Even today, the Hungarians still call themselves Magyars, after the largest of the original seven tribes. The name Hungary comes from On-Ogur, which was the name given to them by their neighbors while still living in the Pontic Steppes. This name translates to “ten tribes.” The letter H was added later by some scholars who believed them to be descendants of the Huns.

2.The Cumans

From the 11th to the mid-13th century, Eastern Europe between the Volga and Lower Danube rivers was dominated by three peoples. These were the Kievan Rus to the North, the Volga Bulgars to the East, and the Cumans to the South. They were a semi-nomadic Turkic group of people who were never politically centralized and lived in a confederation of loosely connected but independent tribes. Nevertheless, they posed a significant military threat to all their neighbors, with their lands extending from the banks of the Danube River in the West all the way to present-day Kazakhstan in the East.

The Cumans first came in contact with the Kievan Rus in 1055 and a few years later began invading their lands, causing much devastation. The resulting war lasted a total of 175 years. They would go on and attack all of their neighbors, including the Kingdom of Hungary, the Volga Bulgars, the Kingdom of Poland, the Byzantine Empire, and all statal entities within the Balkans.

They also played the role of kingmakers, helping the Bulgars and Vlachs gain independence from the Byzantines to form the Second Bulgarian Empire. They also aided the Kingdom of Georgia to halt the advance of the Seljuks and become the most powerful kingdom in the region.

Their end came in the late 1230s and early 1240s with the Mongol invasions. Although the Cumans put up fierce resistance, they were eventually defeated. Their confederation was broken, and the individual tribes were either absorbed or sought refuge with their neighbors. Many Cumans had already settled in their neighbors’ lands in previous decades, most notably in Hungary, where they became integrated into each nation’s elite.

1.The Barbary Pirates

For over three centuries, the Mediterranean Sea was haunted by a notorious group of seafaring raiders: the Barbary Pirates. Named after the Berber tribes of Northwestern Africa, these pirates were the terror of the seas from the 16th to the 19th centuries. While piracy in North Africa had been around for much longer, it wasn’t until the rise of Barbarossa—a legendary pirate leader—that things really kicked into high gear. In the 16th century, Barbarossa united the small pirate states of Algeria and Tunisia under the protection of the Ottoman Empire, creating a powerful network of maritime marauders.

The Barbary Pirates weren’t just a local operation. While most of them were Berbers, they also recruited Arabs, other Muslims, and even some European Christians who’d turned renegade. Their targets? Pretty much anyone sailing the Mediterranean. They attacked merchant ships, raided coastal villages, and captured people to sell into slavery. Their reach was staggering—they struck as far north as Iceland and as far west as the coasts of England, Ireland, and the Netherlands. Entire communities lived in fear of their raids.

By the 17th century, the pirates had upgraded their game. Thanks to a Flemish renegade named Simon Danser, they switched from rowing galleys to faster, more efficient sail ships. This gave them a huge advantage, making them even more dangerous. For centuries, they ruled the waves, and Mediterranean trade nearly ground to a halt because of them.

The United States, tired of seeing its ships targeted, started paying tribute to the Barbary states in 1784 to protect its merchants. But this didn’t last forever. In 1801, tensions boiled over, leading to the First Barbary War between the U.S. and the pirate state of Tripoli. This conflict marked the beginning of the end for the pirates, as it weakened their grip on the region. However, it wasn’t until 1830, when France launched a full-scale invasion of Algeria, that the Barbary Pirates were finally brought to their knees.

The story of the Barbary Pirates is a wild mix of adventure, terror, and history. From their rise under Barbarossa to their eventual downfall, they left a lasting mark on the Mediterranean. If you’re into tales of high-seas drama, daring raids, and the clash of empires, the Barbary Pirates are a chapter of history you won’t want to miss.